The genesis of Handel’s Samson

The season in which Handel premièred Samson, at Covent Garden Theatre on 18 February 1743, marked his final departure from Italian opera and his permanent turn to English word-setting. The last of his more than 30 Italian operas for London had been produced, to small enthusiasm, in 1741. During that summer he wrote Messiah, which he took with him to Dublin and premièred there after two successful concert seasons. He had started Samson before his Irish journey, but he left it in draft till his return, when he considerably revised and expanded it, completing the autograph score on 29 October 1742.

A seed for Samson had been sown well before the start of composition. On 23 November 1739 one of Handel’s keenest supporters, the fourth Earl of Shaftesbury, held a gathering in his London home. The next day he wrote to his cousin James Harris:

I never spent an evening more to my satisfaction than I did the last. Jemmy Noel [his brother-in-law] read through the whole poem of Sampson Agonistes and whenever he rested to take breath Mr Handel (who was highly pleas’d with the piece) played I really think better than ever, & his harmony was perfectly adapted to the sublimity of the Poem. This surely […] may be call’d a rational entertainment.

Shaftesbury’s word ‘sublimity’ to characterise Milton’s dramatic poem is key to contemporary appreciation of art, of Milton, of Handel’s music, and, eventually, of Handel’s setting-to-be. It could well be that at Shaftesbury’s party Handel was inspired not only to improvise aptly on the subject of Samson Agonistes (published in 1671), but to create a major work from it, and to ask his friend Newburgh Hamilton to fashion a libretto for the projected oratorio.

Hamilton was the right person for the librettist’s task. He had a deep respect for great English poetry, and an immense admiration for Handel’s ability to bring fine words to even greater fruition with his music. In 1736 Hamilton had (modestly) arranged for Handel John Dryden’s great ode for St Cecilia’s Day, Alexander’s Feast. Handel’s setting was so admired that (unusually for this period) a full score was published, in 1738. In the celebrated statue of Handel by Roubiliac for Vauxhall Gardens, unveiled in 1738 and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Handel leans on four scores, only one of which bears the title of an individual work: Alexander’s Feast.

Samson was a much more ambitious undertaking than Dryden’s ode, but Milton’s Samson Agonistes was ideal for oratorio, which – as composed by Handel – was not intended to be staged or acted but performed in ‘concert’ style. Samson Agonistes was a drama (‘agonistes’ = struggling), in verse, with named characters. So it lent itself to conversion to recitative and airs modelled, as the solos in English oratorio were, on the forms of Italian opera. Milton intended it to be read in private, not acted, in a genre known as ‘closet drama’, for reading in one’s closet, i.e. study. In order to enable the reader fully to imagine the drama, Milton included ‘stage directions’ (as it were) in the form of descriptive remarks by the characters themselves; Hamilton realised their aptness for ‘opera of the mind’ and incorporated some of them, for example Micah’s comment on first seeing the blinded Samson, ‘where he lies, with languish’d head unpropp’d’.

Milton was aware of early Italian opera, and knew that it was modelled on Greek tragedy. He took Greek tragedy as a model for Samson Agonistes, a basis retained in Handel’s Samson. The structure observes unity of time and place, any physical action takes place ‘offstage’ (such as towards the end of the oratorio), and the drama develops in a series of conversations between two or three people and a chorus which is both engaged with, and a commentator on, the action. From Milton’s drama Hamilton derived a unifying theme of the entire libretto, which gave Handel opportunities – taken magnificently – for imaginative and expressive word-setting: the imagery of dark and light, which suffuses the whole text from ‘Total eclipse’ to the final ‘endless blaze of light’, and is particularly appropriate to the story of a blind man regaining inward light.

Both Milton’s text and the libretto dramatise the encounters of Samson with his friends, his father, his former wife, and his enemies’ champion during his last day on earth, and recount his destruction of his enemies and himself. But Hamilton did a necessary and deft scissors-and-paste job on Milton’s drama, cutting it by two-thirds, simplifying much of its political content, lessening its harsh attitude to women, and taking the character of Samson still further away from his violent biblical original (Judges 13-16). He did more: he incorporated material from fourteen of Milton’s other poems and psalm paraphrases, and added some words of his own, to supply the needs of Handel and his audience. Milton expressly forbids funeral lament for Samson: ‘No time for tears…’, but Hamilton rightly judged that Handel needed a conclusion both cathartic and uplifting, so he added an elegy (‘Glorious hero’) and the famous solo and chorus ‘Let the bright seraphim’.

Even more boldly, recognising that Handel’s style of composition required a succession of contrasting moods, Hamilton created a whole nation to set against the Israelites. Samson opens with a brief recitative in which the blinded and enslaved Samson bitterly remarks that a festival honouring the Philistines’ god Dagon is affording him a day’s respite from ‘servile toil’. Any audience familiar with the prevailing style of eighteenth-century opera and oratorio would expect this recitative to be followed by an air for Samson. Instead, Samson, and Handel’s listeners, are startled by a blaze of orchestral colour and a jubilant chorus, the first in a sequence of airs and choruses from Samson’s captors, the hostile Philistines. The contrast with Samson’s isolation and dejection could hardly be greater. There is no Philistine chorus in Samson Agonistes. Its presence in Samson is a stroke of authorial genius. It enables Handel to avoid uninterrupted gloom and to introduce a distinct style of music – homophonic and breezy, in exuberant dance rhythms – which perfectly conveys the hedonism and thoughtless confidence of Samson’s captors, especially by contrast with the exalted ‘church style’ of many of the Israelite choruses.

Samson in its time

A modern listener is likely to identify Samson as the first recorded fundamentalist suicide terrorist. Nothing would have been further from the minds of Milton, Hamilton, Handel and their audiences. All of them would have known the Old Testament Samson and recognised him as divinely chosen but deeply flawed: admirable as a patriotic protector of his people and ordained champion of the one true God, but an example of the weakness even of great men. Milton would have identified powerfully with Samson, for he too had become blind while serving his nation’s aims, in Milton’s case as foreign secretary in the government of Oliver Cromwell, who like Samson saw himself ordained to combat the heathen.

By the time of Handel’s Samson, the British cultural public no longer condemned Milton as a republican regicide but sympathised with him for his blindness and revered him as the greatest poet in the English language, during the eighteenth century rated far above Shakespeare. For Handel’s public, Milton’s grand, exalted style was the perfect material for the uplifting, ‘sublime’ mood they craved – this was not really ‘the age of reason’ – and which they especially admired in Handel’s music. Milton + Handel was a dream team, as Hamilton recognised and proclaimed in his preface to the libretto:

as Mr. Handel has so happily introduc’d here Oratorios, a musical Drama, whose Subject must be Scriptural, and in which the Solemnity of Church-Musick is agreeably united with the most pleasing Airs of the Stage: It would have been an irretrievable Loss to have neglected the Opportunity of that great Master’s doing Justice to this Work; he having already added new Life and Spirit to some of the finest Things in the English Language.

There was an element of partisanship in Hamilton’s advocacy, reflecting some competition between London’s two leading music theatre composers to annexe Milton. During 1738 and 1739 Thomas Arne had had huge success with Milton’s Comus; Handel had riposted in 1740 with L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. Perhaps Handel was now laying down a challenge impossible to meet, for Samson, uniquely among Milton’s works, provided scope for two aspects of Handel’s genius always cherished by his audiences: his capacity for expressing human emotion, especially pathos, and his ‘sublime’ choruses. Handel was offered a Paradise Lost libretto on three occasions but – we may think very sensibly – never tried to set Milton’s most revered and far less dramatic epic. But he had been urged, in print, to do a setting of Samson Agonistes. A well-known poet, Elizabeth Tollet, appealed to him after he had produced L’Allegro:

One labour yet, great Artist! we require;

And worthy thine, as worthy Milton’s Lyre:

In Sounds adapted to his Verse to tell

How, with his Foes, the Hebrew Champion fell:

To all invincible in Force and Mind,

But to the fatal Fraud of Womankind.

To others point his Error, and his Doom;

And from the Temple’s Ruins raise his Tomb.

In 1743 Milton was not only England’s greatest poet, he was also a national figurehead in British politics. The Patriot Opposition party, campaigning for probity and responsibility in public life, took Milton as one of their touchstones. The core of patriotism in Samson would have spoken to their aims, and Hamilton and Handel dedicated the libretto to the leader of the Patriot party, Frederick Prince of Wales. In 1743 assertive patriotism had a justification which put Samson’s destruction of Israel’s enemies in a particularly acceptable light. Since 1740 Protestant Britain had been mired in a long, confusing, intercontinental war (the War of Austrian Succession), with few and weak allies, against the immense power of France and Spain, an expansionist and Catholic axis. During Samson’s second season of performances, in 1744, on the night of an actual performance of Samson, the French fleet sailed into the English channel, and Britain was saved by bad weather, not the British navy.

The powerful character of the enemy Philistine choruses would have reflected the audience’s anxieties. For those familiar with Milton’s text, the Philistine dominance in the opening of Samson is a surprise; for Handel’s listeners it would have been additionally shocking to hear heathens announce a ‘solemn hymn’ to an idol which they claim to be ‘king of all the earth’ in metres that are anything but solemn, with trumpets and drums – connoting royalty and triumph – and with words recognisably drawn from the Bible, asserting, as did the Catholic powers threatening Britain, that they represent the true religion. Similarly, the confrontation of Israelites and Philistines at the end of Act II may have seemed far too equally balanced for comfort.

The British, ruled by Germans, often voiced a longing for a native leader to save them from their enemies and secure their safety; Samson provided them with the image of one. In a consciously disunited nation, all agreed on the need for unity; Hamilton and Handel deleted all the misunderstanding and conflict of views between Samson and his countrymen that marks Samson Agonistes, merging the aspiration of the hero and his community. Like so many of Handel’s Israelite oratorios that may seem triumphalist to us now, Samson contains much – to us now rather poignant – wishful thinking.

Like other theatre composers of his time, Handel created roles for specific performers, the artists he had recruited for the coming season. His casting for Samson shows him fully aware of the limits and possibilities of his new genre of oratorio. For his lead roles he chose singers who were also leading stage actors, who could convey the drama as well as the sense of his texts, and he fitted his musical characterisation to their most celebrated qualities. He wrote the sympathising friend Micah for Susannah Cibber, renowned for her ability to convey pathos (most recently, in ‘He was despised’ at Messiah’s première). Dalila was conceived, and hugely altered from her hypocritical, deceitful original, for the hugely popular Kitty Clive, whose line in disarming flirtatiousness Handel exploited with unqualified charm. John Beard, creating the first in a line of commanding tenor title roles in Handel’s oratorios, had a theatre identity of manly British patriotism which transferred ideally to the representation, in Samson, of the embattled British nation.

Samson spoke to the British public on many levels, as it still does today, and unsurprisingly it achieved immediate and lasting success. It was Handel’s most frequently performed dramatic oratorio during the rest of the eighteenth century.

© Ruth Smith 2021

| Date of Composition | 1743 |

| Catalog Number | HWV 57 |

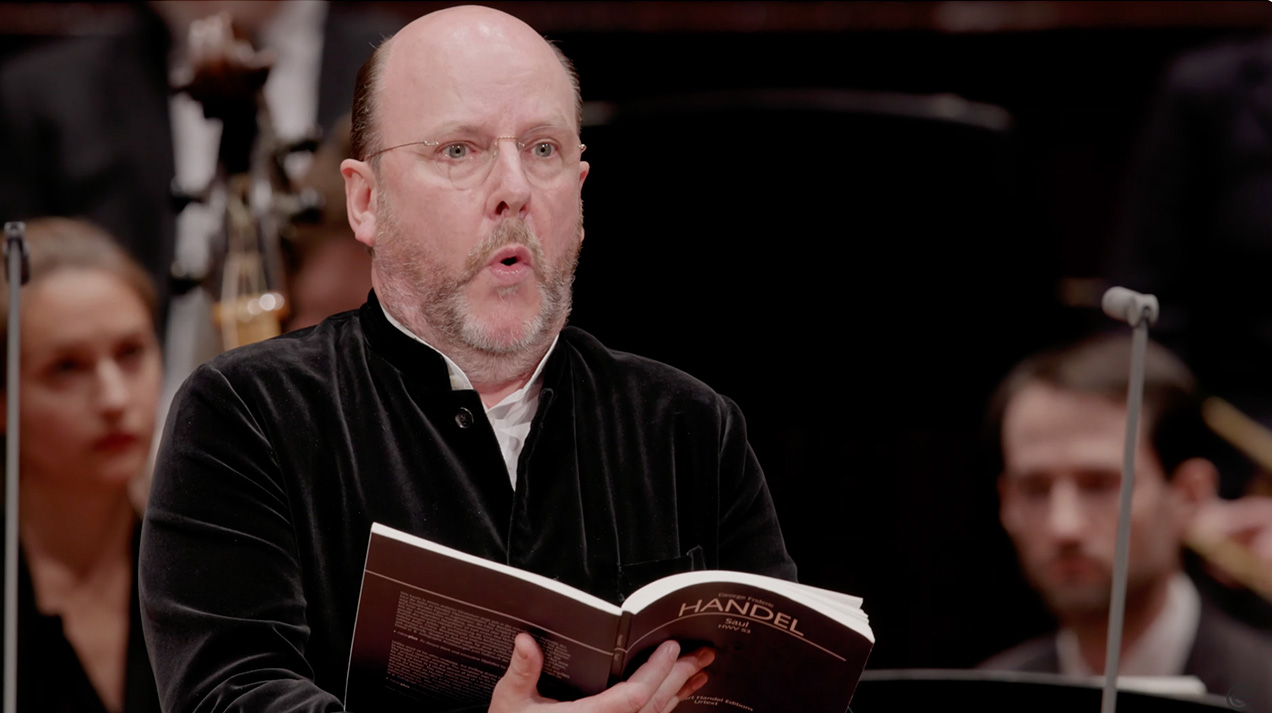

| Recorded | 13th October 2021 as part of the London Handel Festival |

| Location | St George’s Hanover Square, London, Handel’s Church |

| Director | Harry Bicket |

| Samson | Stuart Jackson |

| Micah | Paula Murrihy |

| Manoah | Matthew Brook |

| Dalilah | Sophie Bevan |

| Harapha | David Shipley |

| Israelite and Philistine Woman | Rachel Redmond |

| Israelite, Philistine man and Messenger | Gwilym Bowen |

| Ripieno chorus | July Louie Brown, Helena Thomson, Graham Neal |

| Violins | Tuomo Suni, Kinga Ujszászi, Jacek Kurzydło, Silvia Schweinberger, Alice Evans, Julia Kuhn, Annie Gard, Miki Takahashi |

| Viola | Jordan Bowron, Louise Hogan |

| Violoncello | Joseph Crouch, Jonathan Byers |

| Bass | Ismael Campanero Nieto |

| Oboe | Rodrigo Gutierrez, Sarah Humphrys |

| Bassoon | Inga Maria Klaucke |

| Organ and Harpsichord | Stephen Farr |

| Horns | Ursula Paludan Monberg, Martin Lawrence |

| Trumpets | Simon Munday, Matthew Wells |

| Timpani | Pedro Segundo |

| Video editing and direction | Alfonso Leal del Ojo |

| Sound engineering | Philip Hobbs |

| Keyboard supply | Simon Neal |

| Camera operation | Wash Media |

| Edition | Baerenreiter Verlag © 2012 |

for a new generation.